As a first step we need to be fully there – where we are, where everyone is. And there’s always something else there too, a mirror of yourself, a reflection. Which at times can extend infinitely. So, if we think about Zen practice (rather than forms or techniques), it means that studying the path is studying the self. Our perception of the world is subjective; it isn’t the world itself (just as there’s no one truth) but our perception of it. This doesn’t mean that reality doesn’t exist, but that we see our own perception of it.

Taking these questions into making another group piece demands great openness towards what can happen. If every step and every moment the things we do/perceive can change, the work we’re making can become a slippery ground of transformations and perceptions, and this demands everybody’s full attention to every single moment. This slippery ground needs to be anchored to something solid. In our case is the score, the choreography, which in the wider sense could be seen as a response to what’s happening in the world. In a very open, maybe also dreamy or poetic, fantastic, abstract way. But it can also (only) be seen as an opportunity to be fully present, as a reason to be there, fully there where we are. So in a way the score is a trajectory for practising being fully present, infinitely mirrored by one another, changing our realities moment by moment, breath by breath, layer by layer, motif by motif, movement by movement.

How do these spiritual and poetic aspects interrelate with the physical and corporeal elements in the choreography?

The Shift of Focus as a title notion refers to how we shift our own gravitational centre – and through that our own body weight – in relation to an action or activity. Everybody knows this from daily activities. For example, just before we cut a piece of bread we position our hand differently; we position ourselves behind the knife so that we can use our own body weight and cut without the knife or the bread slipping away. And our aikido master, Gerhard Walter, teaches us to understand what ‘naturally’ happens within ourselves so that it can inform the complex movement in aikido techniques. Ultimately it’s the same for dance, performance or any kind of ‘studied movement’.

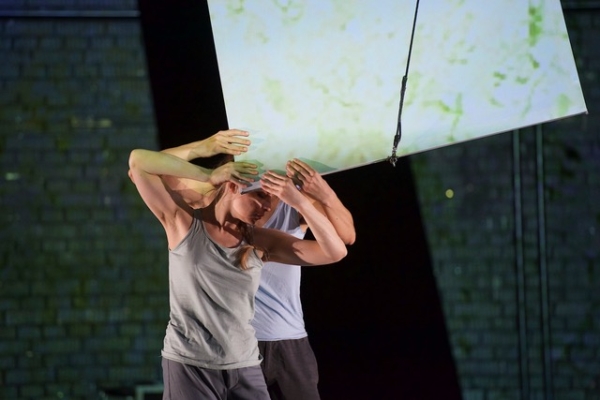

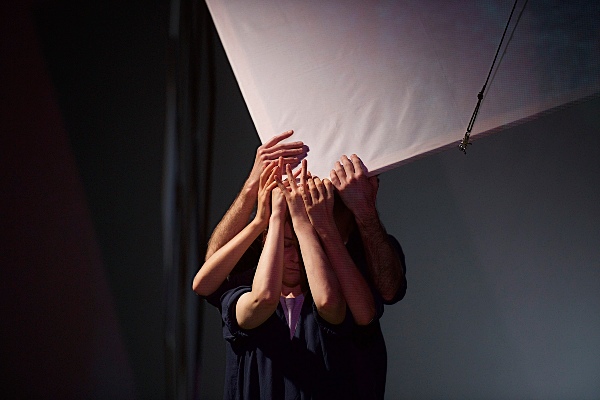

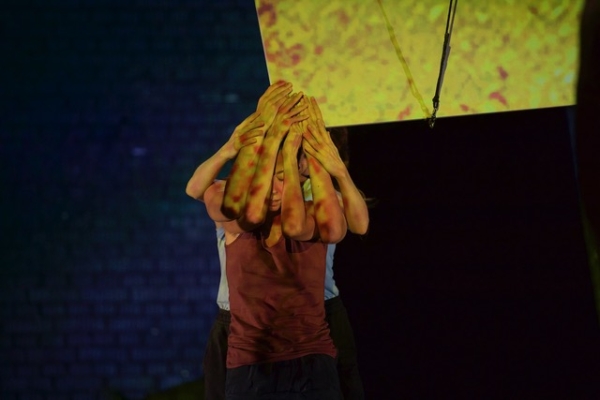

How we position ourselves behind our hands plays a major role, and has to do with how our own centre of gravity informs the resulting spiralling within the body in motion. Through an awareness of gravity in relation to our position we are able to send our energies outward – without forcing – connecting through the tissues, organs, layers, fascia in a kind of infinite spiral from foot to hand and beyond the fingertips. It often reminds me of the dynamic group flow of classical paintings. The work with the movement, and specifically also with the panels – the mobile landscape created by Umberto Freddi – took place within this awareness.

On a metaphorical level I wanted to shift the focus to the forces that keep us together – universal ones – given how hectic and stressful our daily lives have become in these times of war, political confusion or Covid. For me this means a continuation of what I’m busy with already, and it refers to what I said earlier about Zen. Ki can be defined as the universal energy we can all perceive once we bring our awareness to our selves, and from there to the world; ki is what we deal with when we train aikido, shiatsu or other movement principles based on our energetic centres, such as our chakras. I have recently also been dealing with light energy or principles of infinite movements that loop, repeat and transform; movements that connect us to more universal or to more cosmic forces. To forces that exist rather than needing to be invented. We are all part of a greater whole, even if we often forget this as we face our daily problems, worries, activities, lives.

How did the practice with the performers concretely work during the development of the piece?

It isn’t easy to find the right words to describe something based on experience and practice, but I’ll try. If we think about Zen being practised a daily routine – for example in cleaning something – it would mean being fully engaged in the mind with nothing other than this, 100% engaged till it’s done. Full engagement is an attention to detail, and it’s humble. We practise the choreographic modules in this sense as well.

If it’s the study of an infinite movement principle that shows itself in the hands and in its visual rhythm, it’s to this small framework that all the attention goes. And from there bodily experience becomes space, becomes spirit.

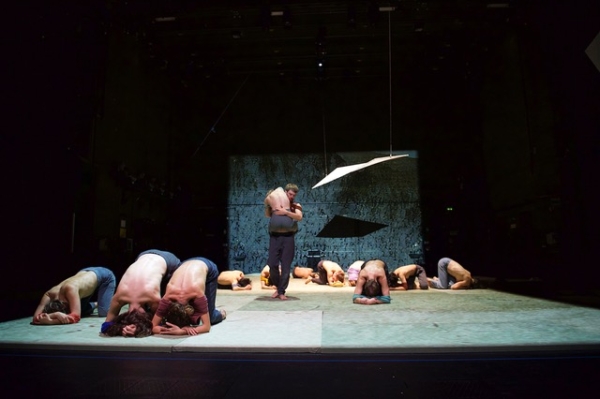

So we work from practice to choreographic understanding, from the rhythm within oneself to the sculpting part – one’s own small framework where the visual rhythm shows and becomes sculpture. And from there to the partner and then to mutual reflection, to the infinite mirroring extending through the space and into the spatial elements, such as the floor modules or the flying panels. It’s a balancing act between zooming in and zooming out.

The Shift of Focus is part of a long-term project of yours which aims to create three different formats analogous to the three classical genres of visual art: still life, landscape and portrait. This piece is inspired by the genre of the landscape. What’s behind this idea of transposition?

I see my work at the boundary between choreography and visual art, where movement – with its coherent perceptions and transformations – is formed and treated almost like sculpture. Working with one person on a solo corresponds to the genre of the portrait; working with a group of people is equivalent to the landscape. In this piece everything needs to be formed as a sculpture. Everything that’s part of the landscape – which is the floor with its tatamis, the flying panels being an extension of the floor to the sky – then the physical work within and between the performers, their voice/breath and sound, light and colour (projection). The difficulty is to see how all those elements at play become ONE. How they contribute to the ONE sculpture, landscape and (fantastic) journey that we send viewers on. On top that the stage apparatus is very relevant again – as much as in Reflection, which was the first work commissioned for HAU1. There I saw no other way than to work with the stage apparatus, as HAU1 is not at all a neutral black-box theatre. It’s a character, and for me it also symbolizes the power we face in the world, be it the power of nature (our planet getting more and more destroyed), the power of war, of a machine gun or any kind of weapon, or the power structure within society, down to the power of bureaucracy keeping us small.

Differently from Reflection, it’s now the vertical axis that interacts with the performers, through strings which they pull or are pulled by. The panels fly up out of view or come from below, just as if we could reactivate the big notions of heaven and hell; just as if we could refer to the ten thousand archetypal figures and stories told over and over again; just as if the Kleistian marionette theatre would come alive again. The vertical alignment somewhat represents the answer to gravity, which is life.

One day master Gerhard said at the end of a class: ‘isn’t it fantastic that it’s lightness which is the answer to gravity and to life.’ It was such a simple conclusion to a complex class that day. I found it really enlightening.

For this piece you have been working with the voice coach Ignacio Joaquin, whose approach is holistic, based on anatomical approaches, visualisation and fascia work. Out of this comes the idea of introducing a chorus into the piece. The term takes choreography back to ancient Greece and to its own etymology. What is the role of the individual and collective singing voice in the piece?

The original concepts of the function of the chorus are really fascinating. The chorus was a tool for the writer to express himself. It often functioned as a way to comment on the plot, to provide an interpretation, express an emotion or give a very personal meaning to the piece.

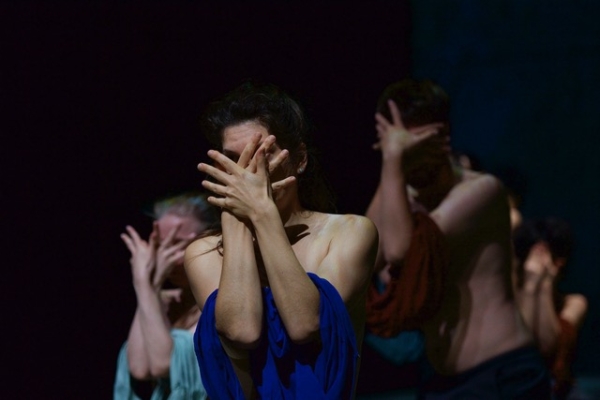

During our working process, the idea of the chorus travelled through all these meanings: not only through the breath and the voice, which is worked in relation to presence and movement, but also by means of rhythm and movement, by creating a landscape, an additional rhythm, an additional weight or simply an overall atmosphere.

Within the chorus, certain protagonistic activities appear, travel, are replaced or merge back into the plurality of the chorus. It’s important for me that these don’t stay with particular persons while others perform the chorus, but that there’s a constant interchange of becoming a protagonist for a certain section and being shadowed by someone else, which is the beginning of becoming part of the chorus again. Replacement systems install a constant interchange of protagonist and chorus between all the performers involved.

I love the idea that this model could be an ideal way of communicating with one another, of creating stories, of undoing hierarchies … allowing for one’s actions to be relevant, to appear and disappear, to support others and to let go.

Speaking about finding ways to coexist and to undo hierarchies brings me to the concept of political relevance, which has been a common thread in all your previous group works: to look at ‘the body as a place of resistance’. Does this also apply to this new work?

I’d almost like to reformulate my own statement and go from ‘body as a place of resistance’ to ‘self as a place of resistance’ – otherwise I’d fall back to separating body from self again, body from spirit or soul, which I see as one unit. One belonging togetherness. So then it’s this notion as such, and the practice of Zen and contemplation, which anchors us in a potentially deeper understanding of how we can be with one another, help each other, relate, be together.

How we can avoid thinking in categories, in pyramidal hierarchies; how we can avoid seeing the ones and the others, borders; how we can empower rather than exploit one another, how we can care for our planet rather than fighting for resources, which brings wars …

When I was trying to explain our practices – related to Zen – I mentioned the notion of what we do making sense, rather than practicing in our little corner, cut off from what’s happening in the world around us. I believe that the paths we take matter. Searching for a peaceful mind, calmness and inner strength, in order to be kind to one another, to connect with one another, and from there to spill these qualities into our daily lives and relationships. I could go on, but I guess everyone knows …

Speaking about how a practice can generate and inform relations between those who share it on a daily base, and by extension also with the ‘outer world’, what kind of connection do you aspire to with the audience?

I want to create pieces that offer a shared contemplative time. And an experience of shared space. The time–space experience is unique and personal to everyone, and yet we also feel something together. When I make work, we always start with a detail that creates the image. The meaning of this image unfolds for everyone within their own journey. For the viewers as much as for the performers. It’s an autonomous way of seeing in which the viewers discover meaning on their own, and perhaps relate the unknown or unfamiliar to their unconscious or their own experience. In the best case, the images created throw you back on yourself, your own breathing, your own perception of self.

For me this is what art can offer, or more personally what I wish to offer: the level of connection as a counterpoint to our daily lives, where we often find ourselves running around with our thoughts jumping from here to there, restless or stressful, sometimes happy but definitely fast.

Maybe it’s just a time for us to rest together and be really present.

Or put differently, the piece doesn’t want to be something but rather to be. It is. Just this.